For many of us, optical illusions are simply a source of fun entertainment. Whether we’re trying to convince our friends that The Dress is actually white and gold or that ‘Yanny’ is quite clearly what’s being said, optical illusions simply give us a few minutes of spirited discussion (or disagreement, as the case may be). The fun quiz element of optical illusions makes it both addictively shareable and something we can’t help but come back to time and time again.

How old are optical illusions, anyway?

Optical illusions have fascinated us for millennia. They go all the way back to the ancient Greeks, with Aristotle noting in 350BC that “our senses can be trusted, but they can be easily fooled”. He realised that if you watch a waterfall for a while and shift your gaze towards static rocks, the rocks appear to move in the opposite direction of the fall of the water. It’s a phenomenon that’s now well known, named (quite aptly) as ‘the waterfall illusion’.

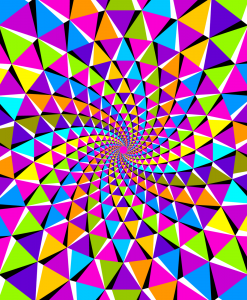

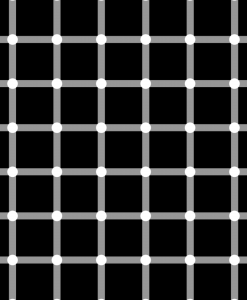

Ancient Greeks also leveraged optical illusions to create the lines of the Parthenon, while Palazzo Spada’s Corridor in Rome uses forced perspective to create the illusion of depth. And, in the 17th century, artist Andrea Pozzo was at work creating a life-sized illusion of a dome in the Jesuit church of Saint Ignazio. Taking it into more modern times, the 1960s saw an explosion of optical illusions, with artists taking an interest in ‘Op Art’ – or optical art – where abstract pieces are created through recurring or contrasting patterns.

Train your brain with optical illusions

Before we go into the science (and we’re about to go heavy), it’s worth pointing out that the term ‘optical illusion’ doesn’t accurately describe what we popularly refer to as optical illusions. Scientists make the distinction between ‘optical illusions’ and ‘visual illusions’. They say optical illusions suggest that the illusion occurs because of issues with the properties of the eye itself. That is, optical illusions are ones that occur inside the eye itself.

Take, for example, floaters. Those small specks, spots or shadowy, dancing shapes that sometimes float into your field of vision are a real phenomenon that occurs within the eye. They’re caused by tiny irregularities in the fluid in your eyes, making this illusion solidly an optical one.

Those illusions that trick, challenge or tease your brain, however, are better described as ‘visual illusions’, because it encompasses your entire visual system from your eyes to the optic nerve to the brain (specifically, the primary visual cortex). Your eye sees the image or video, it travels up your optic nerve, and your brain tries to make sense of it. It’s a similar situation with auditory illusions like the famed ‘Yanny/Laurel’ debate.

Now we’re firmly in the science realm, let’s dive straight into how these visual illusions can help to exercise your brain.

How Optical Illusions Help and Protect Your Thinking

1. Optical illusions encourage better visual literacy.

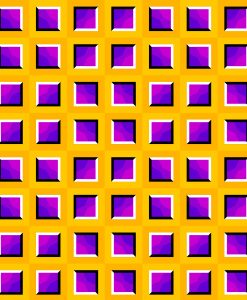

Visual literacy is the ability to interpret and derive meaning from visual information. Much of that meaning is drawn using visual cues that provide context to what we’re seeing. Context helps prime the brain to anticipate what is coming (put together a tree and a blazing summer sun, and you’d anticipate a shadow).

As we view the information, the brain is making connections and predicting the ‘probable’ images that we might see based on what we’ve seen in the past. Many popular optical illusions challenge the brain by presenting the ‘context’ of the image in a misleading way.

Take, for example, the Ebbinghaus illusion where two circles of the same size are shown surrounded by dots, with one of the circles being surrounded by large dots and the other surrounded by significantly smaller dots. Most people will find their brains automatically interpret the dots as being of different sizes. We’ll need to see past that misleading context to figure out what’s actually going on in the image.

2. Optical illusions help us interpret complex images

Another benefit of optical illusions is that it teaches us how to interpret complex images. The ‘My Wife and My Mother-in-Law’ illusion is one such image. It’s drawn in a way that, on first glance, you’ll either see an old woman in the picture or a young woman.

After a while, your brain might be able to re-interpret the image and see the other character (which can, in turn, make it impossible to see the character you initially saw). Studies have suggested that the person you see first could be affected by how old you are, with younger people more likely to see the younger woman.

The more we expose ourselves to different types of complex images, the better our brain gets at interpreting them correctly, beyond the trickery. Our brains are essentially training to see images and objects in different ways flexibly.

3. Optical illusions can demonstrate the health of our brains

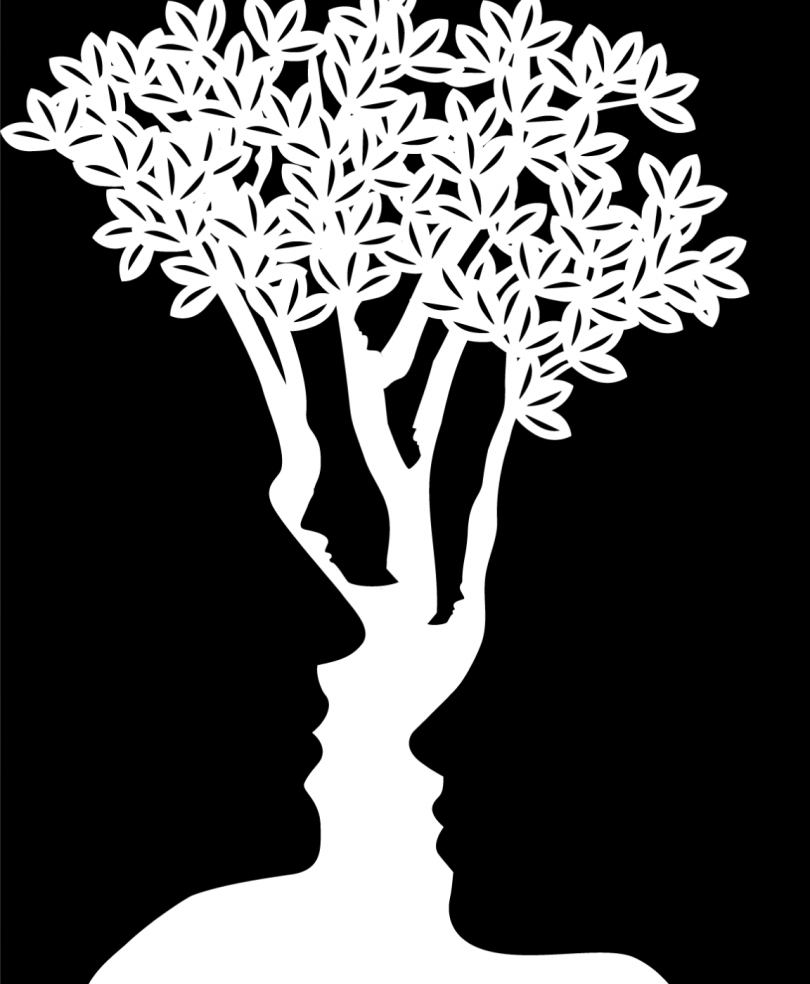

‘My Wife and My Mother-in-Law’, alongside similar images like the duck versus rabbit illusion, the Coffer Illusion and the Rubin vase illusion are all examples of ambiguous images or reversible figures. Ambiguous images are those that have no right answer as to what the image was actually drawn to be. Did artist Kim Jae-Hong intend to draw a praying woman and child or a rocky mountain when he created his famed Woman and Child painting?

According to researchers, ambiguous figures cause the brain (a typical one, that is – the brains of people with autism work in a very different way) to ‘flip’ the way it interprets images. Because both interpretations are equally valid, the brain becomes uncertain and has difficulty choosing which interpretation to go with. So, instead, it decides not to choose. The brain decides to flip from one interpretation to another freely.

A great example of this is Gianni Sarcone’s Mask of Love, a Venetian mask that can be seen to contain either a single face or the faces of two people kissing. You’ll probably find that your brain will pick up on one of those images first, but then will readjust to show you the other one. Flipping gives your brain an advantage – by being aware of both possibilities, the brain can retain two sets of information that may come in useful in any future interpretations it comes across.

However, your brain chooses to interpret the next optical illusion it comes across, at least you can rest assured that it’s getting a good workout in the process – even if it lands you standing alone in the ‘Laurel’ camp.

AUTHOR’S BIO:

Hasna Haidar is a digital researcher and writer, exploring the connection between optical illusions, social media and the human brain.